February 6, 2026

Inside Hunter S. Thompson's wild, boozy week in Houston for the Super Bowl

When the Super Bowl passed through Houston in 1974, it wasn't quite yet the well-oiled capitalistic behemoth that we Americans, ever enticed by the spectacle of flashy commercials and greasy finger foods from our favorite chain restaurants, have become so accustomed to.

It was well on its way, though.

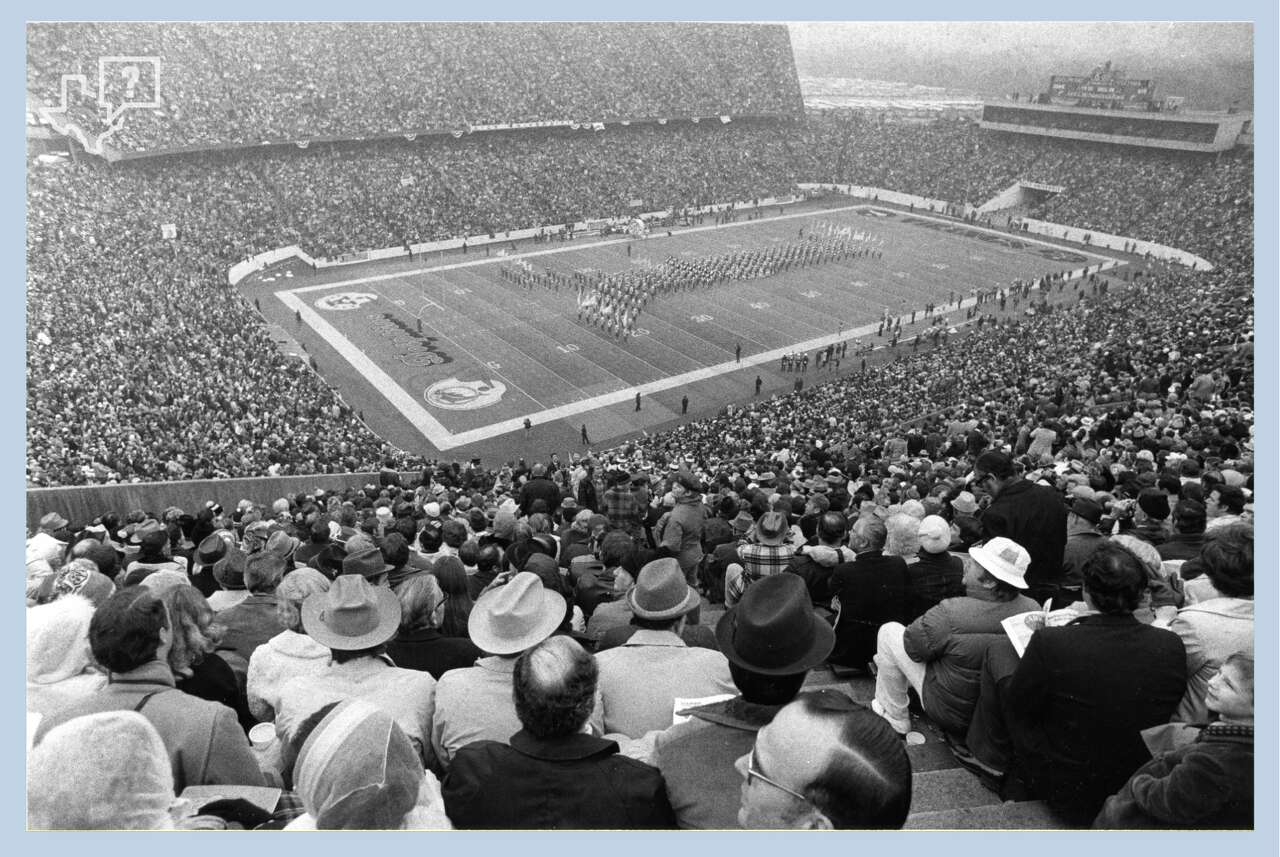

Hunter S. Thompson, the drug-fueled patron saint of gonzo journalism and professional antagonist who later called Houston "a shabby, sprawling metropolis ruled by brazen women, crooked cops and super-rich pansexual cowboys," was here to cover Super Bowl VIII at the historic Rice Stadium. The Dolphins put down the Minnesota Vikings without much resistance on that chilly January afternoon in a dull game.

But it was clear in his dispatch for Rolling Stone, "Fear and Loathing at the Super Bowl," which chronicled his stay in our lovely, yet almost sinister, swamp, that Thompson wasn't in Houston for football but to observe what the Super Bowl was becoming — a traveling pageant of American excess, a media frenzy with sportswriters chasing access (and alcohol poisoning) and a league discovering just how profitable its annual ritual could be.

"For eight long and degrading days I had skulked around Houston with all the other professionals, doing our jobs — which was actually to do nothing at all except drink all the free booze we could pour into our bodies, courtesy of the National Football League, and listen to an endless barrage of some of the lamest and silliest swill ever uttered by man or beast," Thompson wrote.

Houston (and the 1970s in general), in Thompson's telling, felt like a fever dream.

The fog clung to Rice Stadium and followed him out along the Beltway, where he drove across town to watch the Dolphins practice. He wandered through the Astrodome for the NFL's much-hyped "Texas Hoe Down," which he found "wild, glamorous." He slipped out to a strip joint called the Blue Fox on South Main, where a barroom scuffle ended in a blast of mace from undercover vice cops. At one point, he even flirted with the idea of escaping to a cheap motel on the Galveston seawall, as if the Gulf air might clear the haze.

He spent his week and a day staying at the Hyatt Regency, the funny-looking hotel downtown that he described as a "stack of one thousand rooms … with a revolving 'spindletop' bar on the roof." The lobby below churned with "drunken sportswriters, hard-eyed hookers, wandering geeks and hustlers," while upstairs the wind pressed gray mist against the windows.

Thompson was, yes, taking stabs at his and his colleagues' debauchery, and the league's largesse, of course, but he was also laying bare for the first time something that now feels permanently branded into the American experience: that the circus was the point.

And Houston, in this instance, and again every time that a major sporting event rolls into town, whether that be a Final Four or a Super Bowl or a College Football Playoff championship game, was the anything-goes festival grounds where the league pitched its tent and force-fed the city the revelry it was unleashing upon it.

"Whatever was happening in Houston that week had little or nothing to do with the hundreds of stories that were sent out on the newswires each day," Thompson wrote in his Super Bowl bulletin.

(And I expect much of the same when the globe descends upon Houston for the World Cup this summer. But back to 1974.)

Thompson described what he saw and felt in Houston as an "unholy trinity" of God, government and the National Football League, three forces that were revealing just how much they had bled into one another. The drunken sermons he described, packed with the language of "discipline," of loyalty, of righteous victory, served as a parody aimed at a country that was already treating football like religion.

In 1974, that fusion of football, politics and piety must have felt novel, even absurd. Today, it's unescapable, and still just as absurd. The Super Bowl is more of a cultural and political extravaganza than ever, with the league facing more partisan scrutiny for its choice of who will perform at halftime than a cabinet appointment would receive from the United States Senate.

More than fifty years ago, taking in a Houston invaded by fog, Thompson caught an early glimpse of the machine being built around us, right in front of us — the money-making mammoth that better serves as a national corporate carnival beamed directly into our living rooms. He understood that the spectacle was not a sideshow but the product itself, something the league would refine, that cities like Houston would keep its doors open for and beg on its hands and knees to host so that it could borrow the glow for a week or two before the lights dimmed, the buses filled with fans pulled out and the circus disappeared.

Eventually, the machine will circle back through town, as it did in 2004 and in 2017 when the Super Bowl returned, and the day that Houston is chosen to host another, we'll be ready to do it all again, fully aware of the circus, even amused by it, still skeptical of it and tuning in anyway.

| Jhair Romero, Houston Explained Host |

Unsubscribe | Manage Preferences

Houston Chronicle

4747 Southwest Freeway, Houston, TX 77027

© 2026 Hearst Newspapers, LLC

No comments:

Post a Comment